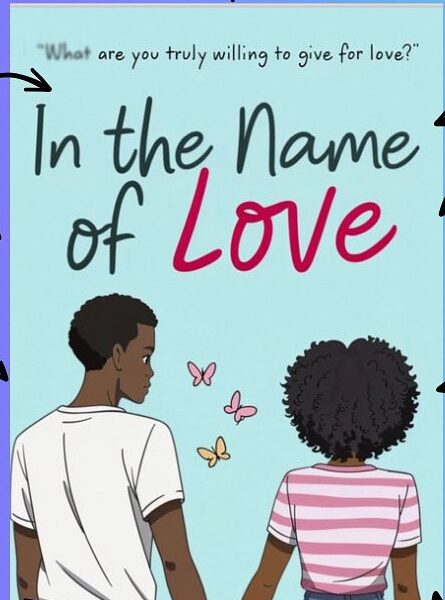

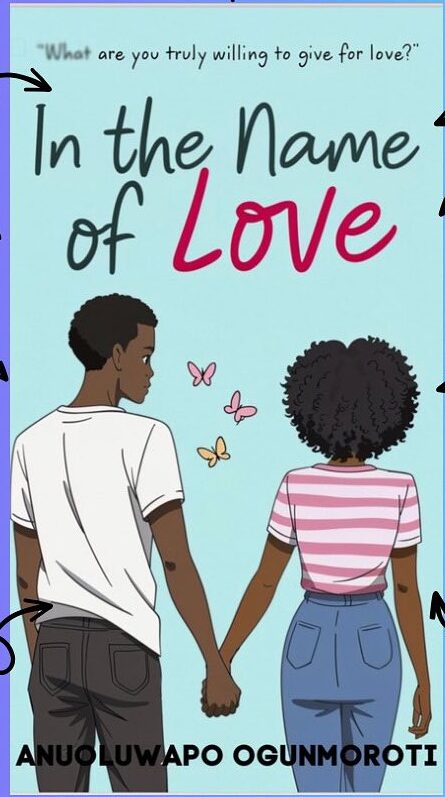

Anuoluwapo Ogunmoroti, a creative and multi-talented Mass Communication graduate of the University of Lagos, a content creator, poet, podcaster, copywriter and screenwriter, has, in her debut novel, In The Name of Love, attempted to tell a story through a non-linear narrative. Ogunmoroti lets the story unfold through poetry, prose and a stage play set up between the characters. In the Name of Love is a hybrid novel that tries to show the beautiful ways art and life can intertwine. The book is an easy read, especially for readers who enjoy Wattpad stories or want a gentle escape from the heavier themes often associated with Nigerian literature.

The novel follows the story of Koriola, a 23-year-old aspiring actress living with her supportive mother in UNILAG’s staff quarters, trying to land her first big role. At her 118th audition, she meets Griffin Adesina, tall, not her type, irritating, and mischievous. What begins as mutual dislike slowly becomes something more when they are cast as romantic leads in a school play. Both characters often behave like teenagers, which some readers may find endearing or slightly exasperating—especially given that Koriola and Griffin are 23 and 22. Still, their dynamic might keep readers turning the pages.

Structurally, the book flows like a performance: part theatre, part Netflix coming-of-age drama, part poetry slam. It is an innovative and refreshing approach, especially in a literary market still hesitant about hybrid storytelling. The novel makes a genuine effort to document the realities of theatre, from chemistry readings and long rehearsals to the emotional and physical toll theatre performances take. While I don’t think it fully succeeds in executing its form, it serves the narrative to some extent. The characters themselves find it difficult to fully interpret the poems into a script, and articulating this kind of struggle within the narrative feels honest and might be intentional.

What particularly draws me to this book, apart from its simplicity, is the family dynamic and the setting. The protagonist lives on a university campus in Lagos with a mother who is also an actress and sees Koriola Macaulay as an extension of herself. Often, when parents believe in their children’s dreams or push them to follow in their footsteps, it is met with resistance. Here, we see the opposite. Koriola is happy to follow in her mother’s footsteps, even though she finds her dramatic.

Another thing worthy of note is that instead of using only traditional dialogue, Anuoluwapo includes eleven poems to handle much of the emotional buildup in this book. Through poems like I Won’t Let Go, Pain With Pleasure, and Trouble in Paradise, among others, we meet Katrine and Zion, the fictional lovers at the centre of the play. More importantly, we see Koriola and Griffin play these characters as well as witness their off-stage chemistry as they embody these roles. The deeper they get into these verses, the more they begin to question where their roles end and their true feelings begin.

Some of the supporting characters bring both heart and friction to the story. There’s Raven, Koriola’s witty, relatable best friend, who’s juggling a 9-to-5 while chasing her acting dreams. Jacob, another aspiring actor—charming, maybe a little too into Koriola—brings tension to the story. Then there’s Mariana, the over-the-top director with a hilariously fake British accent. Each one contributes to the progression of the story. That said, the book does wander in the middle. Some scenes feel repetitive, and characters like Raven and Jacob could have benefited from a more elaborate backstory.

In The Name Of Love explores themes like the messiness of love, grief, intimacy, and often complicated familial relationships. Koriola is affected by her late father, and the void his absence has left. It is obvious that his absence shapes her and affects her relationship with other characters in the book. The novel also handles sensuality, especially through poetry. In some poems, Anuoluwapo writes about female desire without shame or disguise. The characters yearn, touch, moan, and climax unapologetically, in a way that shows women yearn too and carry passion in their bodies.

This book also exposes campus romance while asking real questions about the roles we play and who we really are when no one is watching. The novel reminds us that the most authentic performances sometimes happen when we stop pretending. It also further presents the kind of upper-middle-class Nigeria many young people imagine: a clean Lagos where NEPA never takes the light, there is no traffic, and class politics or police presence never interfere. It prioritises comfort and aspiration over realism. I appreciate that the dialogue captures the texture of Nigerian urban youth speak, very on-brand for a generation fluent in pop culture.

Anuoluwapo takes a welcome risk with this novel, which I believe will resonate with young readers drawn to stories about art, self-discovery, and cheeky romance in a glorified campus setting. If you’re into the enemies-to-lovers trope, this one’s for you.